There has been a ton of information out there on Docker over the last week. Because the impact on networking is often overlooked for new technologies, I figured I’d get a head start to understand the basics of Docker Networking. This post documents the steps I took to test docker analyzing the network constructs that are automatically configured during container creation.

First, I installed Docker using instructions for Ubuntu 12.04 (LTS) 64-bit.

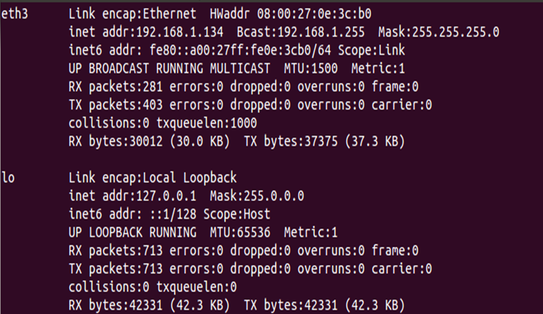

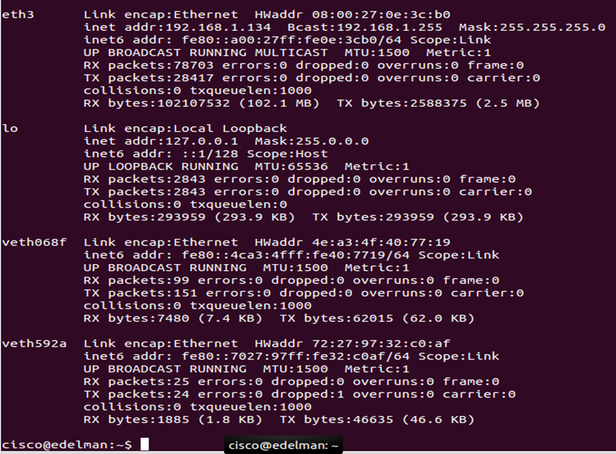

Post install, but before a container was created, here is the output of my Ubuntu machine. Two interfaces: eth3 (192.168.1.134) and lo (127.0.0.1). This Ubuntu machine is running in virtual box and eth3 is bridged onto my home network of 192.168.1.0/24.

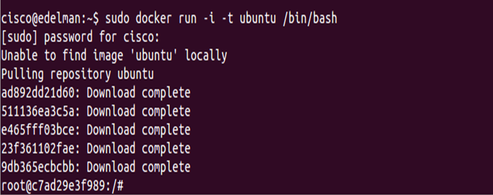

Creating my first Docker container. This took about a minute (maybe less) to download and start. Pretty impressive. Notice the last line in the screen shot below. It takes you right into the container shown at ‘root@c7ad293f989:/#’

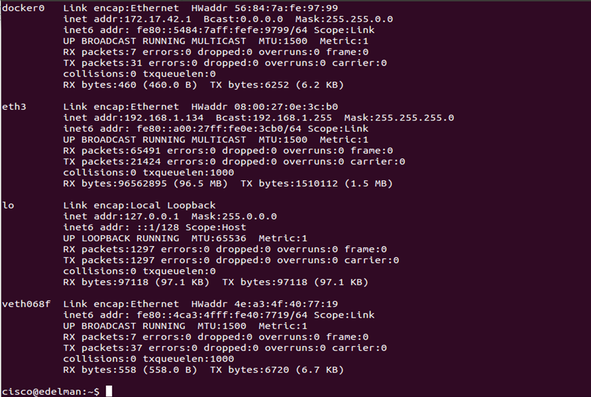

In a new bash prompt because the existing shell is now used for the container, check out an ‘ifconfig.’ Notice the two new additions: docker0 and veth068f. docker0 is a Linux bridge and veth068f is an interface on that bridge. Docker picks a subnet not currently in use on the machine and assigns an IP in that range to the docker0 bridge (these are just the default settings).

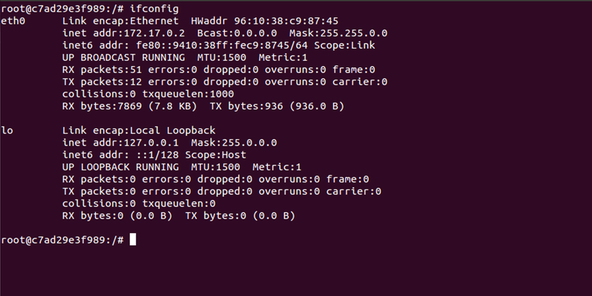

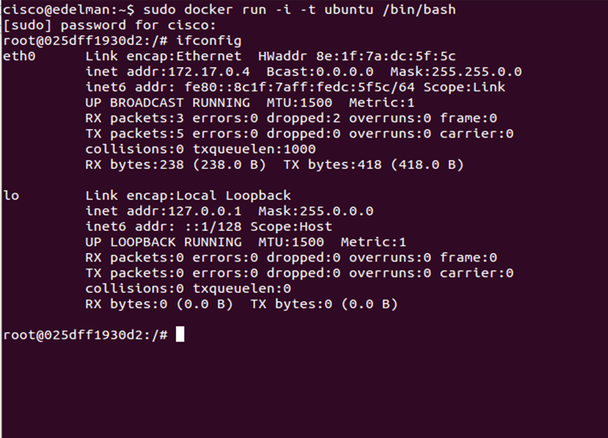

Going back into the container, let’s issue an ‘ifconfig’ there. We can see ‘eth0’ was automatically created. This seems to be a patch port that directly connects to veth068f in the docker0 bridge. Notice the subnet is a /16 and still in range of the IP assigned to docker0.

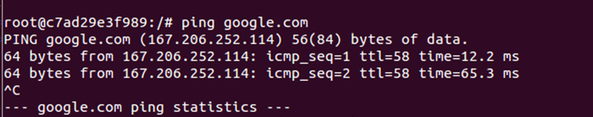

At this point, pings are successful to the Internet. See the screen shot below. But how is this happening?

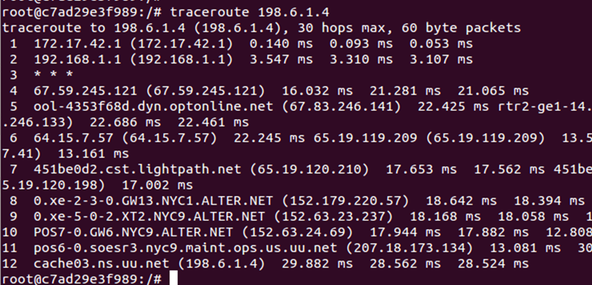

Let’s check to see what the default gateway of the container is. It is in fact the IP Address of the docker0 bridge. This can be seen in the following traceroute.

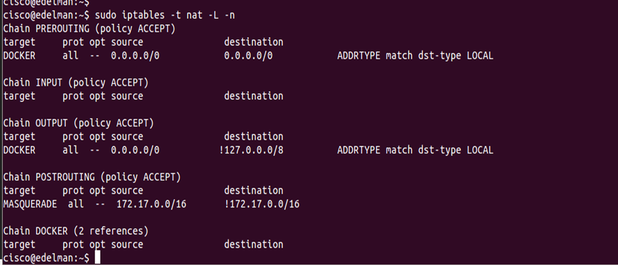

But where is NAT is configured? I don’t have NAT configured in virtual box. As I said, this is a bridged Ethernet adapter on my Ubuntu VM running VBox. It turns out Docker auto configures ip tables to allow outgoing connections and NATs them to the docker0 address. You can see this in the ‘masquerade’ statement rule below.

Few things worth noting:

- No inbound connections are permitted by default

- You can in fact remove docker0 and use your own bridge.

- Because you don’t need to use docker0, it should be fairly easy to integrate with network virtualization solution that use a different bridge like ‘br-int’ as I talked about here.

- Cloud Management Platforms such as OpenStack would just need to support Docker to give the right information to ‘neutron-server’ such as MAC address, port, IP, etc. in order to properly configure required overlay tunnels and interfaces

- Follow this link for more advanced networking with docker. There is plenty more that has already been documented by Docker.

Below shows two more screen shots creating a second container and the testing of its network connectivity. Because the container image was already downloaded, this container was literally created in under a second.

Notice the new interface on the docker0 bridge, veth392a.

Connectivity was successful between containers and from the new container to the Internet.

The goal here was to give a very high level overview of networking with Docker although there is plenty more that can be done. In the future, I would like to test with OVS custom bridges and get more creative with the L2/L3 designs, but there is only so much time in the day! Stay tuned for more!

Thanks, Jason

@jedelman8