In the previous post, I talked about a common programmable abstraction layer (CPAL). To better understand the thought process behind having a common PAL, it makes sense to review some of the work Jeremy Schulman has been doing. Jeremy often refers to the Python interactive shell as the new CLI for networking. When you watch him give a demo using the Python shell as a CLI, it is second nature and looks exactly like a network CLI. It makes perfect sense.

It gives real time access to the network devices in a programmatic fashion. Being programmatic is key here – no screen scraping, etc. The downside — you need to know Python. Well, yes and no. Of course, you would be using the Python interpreter so you’ll be leveraging programming concepts – things like variables, functions, classes, etc.

But, before you think you need to become a professional software developer, the other good news is that Jeremy has created the Junos OS PyEZ library that drastically simplifies the interaction and baseline knowledge to start programming Juniper devices. Juniper supports native XML APIs, but the PyEZ module abstracts that and eliminates the need to be knowledgeable about Juniper-specific XML APIs. As you can see directly in his own words here, the PyEZ library was built for two-types of users, non-programmers who may just use the Python interpreter as their new CLI, and also for full time programmers who want to automate and program the network infrastructure, but need a programmatic way to work with the network.

Sample output below using the PyEZ library while on the Python shell, i.e. the new network CLI. source: https://github.com/Juniper/py-junos-eznc (compliments to Schulman again)

Bit more background leading up to this point…

A few months ago, I built a Cisco onePK application using the Groovy/Grails framework. This gave me a good baseline around the onePK framework, but also got me into reading the detailed Java docs that define all available classes, methods, associated constructors, etc. It was mind numbing in the beginning, but it slowly grew on me. After a break from onePK for a few months, I picked things back up last month when the Python SDK for onePK was released, or at least put in controlled availability. Now it was looking at PyDocs and diving a bit deeper into Python. There is a learning curve here for sure with onePK, and it’s been a fun one for me personally, but as I was working with onePK, I knew this needed to be simplified if network engineers at the masses were going to adopt something like this. It is just too much to consume if all you really need is quick and dirty scripts on the network. So what gives?

I remembered one of the features Jeremy had in PyEZ was getting “facts” out of the Juniper devices very easily (see picture above). I had recalled him typing on the Python shell ‘device.facts’ (turns out it was really dev.facts) and it returned a list of facts about the device – this included hostname, serial number, etc. That was cool and this is generally what is needed with onePK. onePK essentially needs to be hidden!

There are some funky things with having to create an application instance with onePK and the same application can only connect to a device once — yada yada. This is stuff that can easily be abstracted out so the user who wants to use the Python shell as their CLI shouldn’t have to worry about the intricacies of onePK just as the user of PyEZ isn’t worried about the details of Juniper’s XML API.

About two weeks ago, I created a small module called cpal.py that abstracts the complexity of onePK, but still offers the full power of onePK. Without really knowing it at the time, it was created largely for the same reasons Jeremy created the PyEZ library. However, the PyEZ module is much more robust and feature rich than CPAL! CPAL only has some “facts” right now, but the point is about the platform and what it can offer longer term.

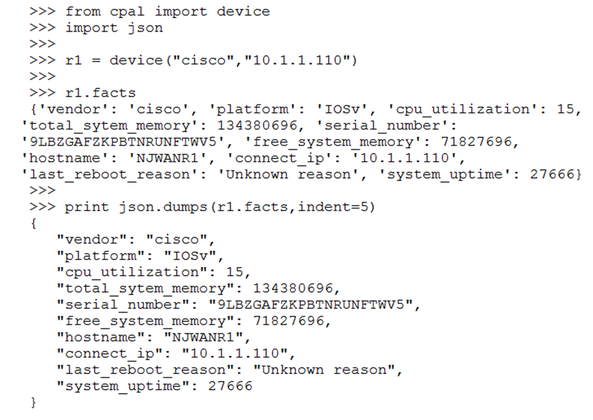

CPAL with Cisco onePK

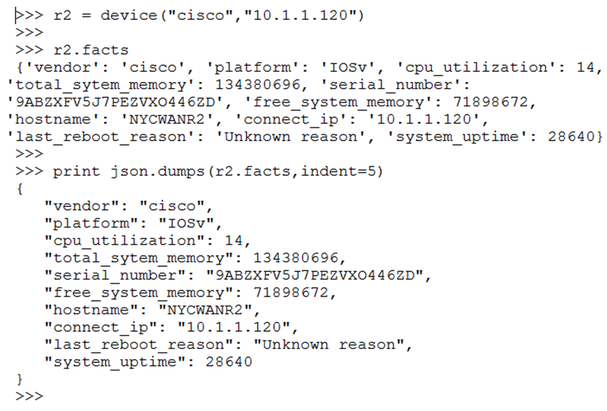

Adding a second router:

Does that look similar to the PyEZ module at all? Network objects are being created and facts about them are being displayed! It’s as simple as that (for now). These are in fact Cisco routers leveraging onePK, but you would never know it with this layer of abstraction.

A Common Programmable Abstraction Layer (CPAL)

By now, you can probably see where I’m going with this. Why stop with Juniper and Cisco devices? Why not have a library for each major device type and create a true and common programmable abstraction layer?

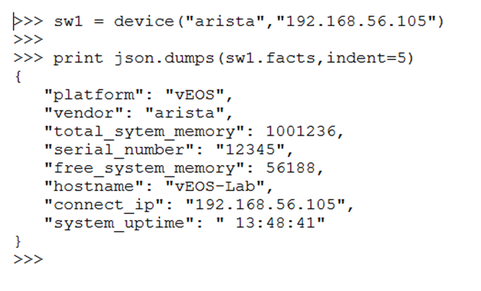

Adding in Arista’s eAPI

The Common Programmable Abstraction Layer (CPAL) normalizes device specific APIs such as Juniper’s XML API , Cisco’s onePK, and Arista’s eAPI. Actually, Juniper’s isn’t integrated yet, but could be fairly easily.

At this point, I would argue having a CPAL like based SDK simplifies things and reduces the learning curve because it’s possible to quickly leverage dir() and help() within the Python interpreter to get assistance. Side bar…For pure REST APIs, you don’t have that kind of immediate feedback directly at the CLI/shell. If the data you need isn’t there, a module can quickly be built to offer a certain feature. Of course, this is my opinion for now — it’s not to say it won’t change after testing more APIs /SDKs, but it’s just one reason I’m inclined to favor language based SDKs vs. REST APIs. Some argue that an SDK based on a clean REST API is the way - sounds good to me.

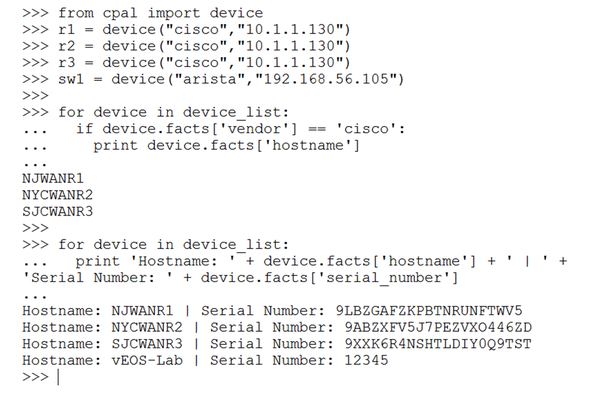

CPAL with Cisco + Arista Working Together

To really make sure the point gets across, check this out interacting with a combination of Cisco and Arista devices in a programmatic fashion:

Did you notice each one of those small scripts is just three lines of code (minus creating the network objects)? The first one is showing all cisco devices and the second one is displaying all device hostnames and associated serial numbers.

Note: with an abstraction layer as discussed here, the vendor can change their APIs, or you can even change the hardware deployed, and nothing would need to change with the way you interact with the network. For example, you could use onePK today, but Cisco’s RESTful API in the future, and nothing would change for the actual end user. All that would be needed is a new module (on the backend).

From a device API perspective, as mentioned already, Juniper has XML APIs, Cisco has onePK, and Arista has eAPI. On newer devices like the Nexus 9000, Cisco will be offering native REST (XML/JSON) interfaces on devices and also giving direct access to the Linux shell. Arista also gives access to the Linux shell in addition to eAPI. Cumulus, on the other hand, only gives access to a Linux shell.

Linux Network Programmability

There is a feeling of openness being able to directly access a Linux shell on a network switch. The opportunities are limitless with what you can do and you are not bound to what a vendor exposes for you. While this is true, from a programmability standpoint, you are at ground zero. No default APIs exposed. While you can load your favorite configuration management tool on the device since it is native Linux, that doesn’t help if you need a way to programmatically interact with the devices. This begs the question, which devices types are more programmable? It will depend on level of expertise of course, but for the average network guy, it likely won’t be the device that just offers access to the Linux shell. As seen in this post, the samples were using vendor specific APIs normalizing them in a common fashion. The next step would be to have a python module that can do this natively for pure Linux interfaces, again, with the goal to offer users a programmatic way to interface with all network devices!

At this point, you can see this is just scratching the surface with what is possible. Something like a common programmable abstraction layer is all about having a vendor independent interface to easily “program” to network devices. Otherwise, we just end up with even more APIs than we have CLIs today, which gets us nowhere. At the same time, this allows the Python shell to be used as a network CLI, but also allows full blown automation frameworks or applications to be built using a CPAL that is normalizing vendor specific APIs. And don’t forget, the native device API would still be accessible via something like CPAL.

Maintaining The Power of the Native Device API

To convey what can be done, the focus here has been to show device facts and quickly iterate through the devices looking for particular information. What if CPAL actually doesn’t have a function for something that the native API supports? Easy - it remains exposed via a variable that is accessible within the vendor’s module. For example, we created an object called r1 that represented a Cisco router running onePK. To access the full breadth of what onePK can offer, it can simply be called using ‘r1.native’ — in onePK speak, ‘r1.native’ is of type NetworkElement. The same holds true for Arista’s eAPI above as well. Pretty cool, right?

SDN Controllers

Few points to make…

- While SDN controllers weren’t mentioned in this post, they can easily be included. CPAL would look like an application riding on top of the controller. It would be more analogous to the Arista example since they are using REST. By integrating a controller into a framework as being described, it would streamline the way applications and tools are built that need to communicate with isolated network devices and SDN controllers that may or may not have standard northbound APIs.

- Having something like a CPAL is not to replace a controller by any means – for example, how do you quickly interact with a network device leveraging the Python shell with a Controller today?

- CPAL could be seen as “semi”-analogous to OpenDaylight’s Service Abstraction Layer (SAL) as it is a layer of normalization, but something like CPAL is all about offering flexibility and programmatic access to the network using a dynamic programming language like Python without necessarily needing a controller, but if there is one there, great!

On that note, it’s about time to bring this post to an end! If you made it this far and wish to see the CPAL source code, you can check it out here.

Edit 3/15/2014: Github repo for CPAL

What do you think? Does something like CPAL make sense to pursue? Always looking for input and feedback.

…And be sure to check out the demo of CPAL here…

This post didn’t cover one native API vs. another like onePK vs. eAPI, but hopefully that can be an upcoming post. If that’s of interest, let me know!

Thanks, Jason

Twitter: @jedelman8